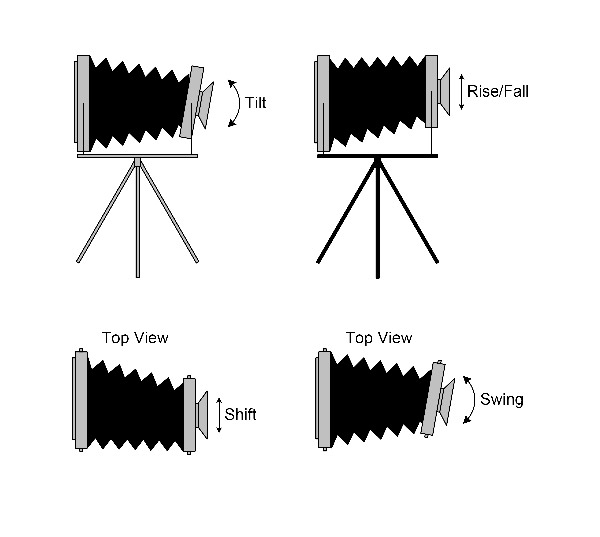

Swing – Tilt – Rise

The front and back panels (called ‘standards’) move independently of each other in a series of movements called rise, fall, shift, tilt and swing. This gives the photographer control over converging verticals, the plane of focus, and depth of field within the image.

In view camera photography, one of the most vital image controls is the ability to expand (or, in some cases, contract) the degree of sharply focused detail within a composition through the use of swing and tilt movements. In a camera without movements, the range of sharp focus (depth-of-field) is controlled strictly through lens aperture and focal point. Large apertures have relatively narrow depth-of-field and smaller apertures have a much greater depth-of-field. The closer the photographer focuses to the camera, the narrower the depth-of-field becomes at any given aperture. The detail is inherently less sharp the closer you get to the camera (forward of the focal point) than it is further away from the camera (behind the focal point). Hence, the rule of thumb is that to maximize depth-of-field, focus 1/3 of the way into the range of intended sharp detail and then stop down accordingly. But, with the view camera, photographers have the capability to actually re-align depth-of-field to a specific subject plane.

Swings and tilts are used to hold a receding plane in focus, or (more rarely) to isolate a narrow plane of focus and throw the rest of the image out of focus. We find it easiest to think of swings and tilts in terms of focus. When you focus closer, you wind the lens further out. Now, imagine that you have two subjects at different distances, both of which you want to stay in focus. You need the lens focused at two distances at once: one nearer, one further.

When axis swings or tilts are employed on the rear standard of a view camera, the focused image becomes unfocused everywhere except at the axis of movement, because the distance between lens and film remain constant only at this point. The photographer then has to refocus to see if the movement achieved its intended effect. (If you use base tilts, the entire image becomes unfocused because no part of the film plane maintains a constant distance to the lens.) Sometimes it may be necessary to go through the procedure of focusing, swinging/tilting, and then refocusing a few times before the desired effect of overall sharpness along the subject plane can be verified on the ground glass.

A couple of general guidelines to consider are that asymmetrical swing/tilt movements are typically used only when the camera position is at an oblique angle to the subject. The more oblique the angle, the more important the movement is to expanding depth-of-field. Second, the subject must conform predominantly to a two dimensional plane. Angled views of a picket fence, the facade of a building, the surface of a table, a wall, etc. are all good examples of the types of subjects where swings and tilts may be employed to increase depth-of-field. Another important consideration is that, as foreground or background is initially focused at the axis of movement, the subject detail along this line should be in approximately the same plane. If it isn’t, then the movement is not likely to re-align the depth-of-field beyond what could be achieved by merely stopping down. Finally, the marked axes of movement are only relevant for the primary format of the camera. If you use a reducing back, for roll film for example, then the lines that identify the axis of movement will not be accurate for the reduced format.

New South Associates’ photographers have an eye for the movements and angles that can be created in a large format camera. We can use our expertise to make your resource look amazing while also showing the importance of the structure through angles and setting.